Friday, 15 June 2012

Ruins as Memorials

http://ragpickinghistory.co.uk/2011/06/05/ruins-as-memorials/

RUINS AS MEMORIALS

5062011

1 Votes

England’s Peak District is a beautiful area of wild moorland and wooded valleys; but it’s also a graveyard for over 50 aircraft – mainly Second World War planes that crashed in poor visibility on the western edges of the Peak’s bare moorland. These tragic remains now attract ‘baggers’ in the same way that the Scottish mountains do and there are many websites and even books listing the wrecks and their precise positions in the often featureless landscape.

I came across my first wreck by accident, while trying to find my way over a desolate stretch of moorland in the area around the Black Hill in the far north of the Peak District. First, I came across single pieces of metal (1), shredded and twisted, and then, following their trail, I found recognisable parts of aircrafts – bits of wing, engine and fuselage – heaped together in a shallow gully. Finding this wreckage suddenly invested the landscape with a enigmatic sense of tragedy – an unknown story that obviously involved violent death. More striking was the discovery of a small memorial – a cross and a poppy – embedded in part of the wreckage (2). After returning home I found out the story of the wreckage: two Meteor aircraft had collided in mid-air in 1951 and crashed on the moorland, killing both pilots.

Many of the Peak District’s aircraft wrecks are also memorials. A much larger wreck at Higher Shelf Stones near Glossop is very close to a popular walker’s path and it consists of the ruins of a B-29 aircraft, which crashed in 1948 killing all 13 people on board (3). Amongst the wreckage – including almost intact engines, wings and wheels – are countless memorials, made up of a mixture of crosses, using stones gathered from the moor (4), bits of wood or even parts of the wreckage itself, and poppies arranged around the engine parts in scarlet wreaths (5).

The iconography of these memorials is the same as those used for war memorials and many of the aircraft were used during wartime or carried veterans when they crashed. Yet, the effect of this iconography amongst these wrecks is very different from its more common counterpart – that is, cenotaphs and poppy-wreaths that form the focus for acts of civic remembrance. Here, unchanging ceremonies present the past as if it were static, undisturbed by the erasing nature of time and the duplicity of memory. In these Peak wrecks the memorials become part of the ruin: wooden crosses are scattered by the wind(6), poppies devoured by rain, stones sunk into the bog. As such, even as they bring to mind past lives obliterated by a violent event they also participate in the inevitable process of ruin itself.

We might even argue that the wreckage itself is a more powerful memorial than the later additions. Left where it fell in the landscape, it is overtaken by nature: the metal surfaces become strangely contorted by rust and weathering (7), moss and grass grow through the pierced surfaces, and sheep make use of hard surfaces as convenient places to relieve an itch (8). In its ruined state, this wreckage speaks both of a past event – one that is tragic and violently immediate – and of its subsequent return to a much slower time, where it accumulates the stories of the landscape itself.

Rosamond Purcell's Bookworm

http://compassrosebooks.blogspot.com/2011/06/rosamond-purcells-bookworm.html

SATURDAY, JUNE 25, 2011

Rosamond Purcell's Bookworm

Some years ago, I recall seeing mention of photographer Rosamund Purcell teaching a Zone VI workshop. Zone VI was the brand name for a view camera equipment marketing outfit--the brainchild of a photographer named Fred Picker--which sold cameras and tripods and other accessories, mostly by mail order, in the 1980's and '90's. Some of the equipment was good, but not everyone was satisfied with the merchandise. Picker was a big promoter of his own photographic work and his product line. With the decline and impending demise of straight silver process photography, Picker's business fell on hard times. He died in 2002 after a long battle with kidney disease.

But Picker isn't the subject of this blog.

Rosamond Purcell [1942- ] has become widely known through her publications, including among others Illuminations [1986, a collaboration with the late Stephen Jay Gould]; and Owl's Head [2004], and most recently, Bookworm.

Purcell's work has focused primarily on the artifacts of natural history, as a starting point, and over the last several years, on the vivid and immediate visual properties of organic decay. Preservation and disintegration, as metaphors for meaning in photographic imagery. Purcell isn't the only one exploring this kind of imagery, but she's done as much of it, and with more penetration, than anyone else I can think of. Her work has obvious affinities with--for instance--the boxes of Joseph Cornell. Her photographic images often seem like dense arrangements of rotting matter, odd paraphernalia, curios, keepsakes, found objects,--the detritus of gratuitous potlatch--in various states of unkempt decay or breakdown into constituent components through oxidation, consumption by pests, degradation by fire, dampness, pressure, the ravages of time and flux.

That ordinary objects may hold the evidence of all this energetic use, on the one hand, or of their abandonment and neglect, on the other, is one of the truisms of her art. Bookworm [2006] is devoted to an exploration of the minutely recorded evidence of the decay of written or recorded matter--or books--or other related surfaces which exhibit the fragmented or riddled traces of their original form. The bookworm becomes a philosophical key to the 125 color images in the book--bookworms literally eat their way through books, putting holes in them, like cheese. But of course, there are many forms of decay. Our culture's latest disregard for the inherent values of the material text, at the dawn of the Age of Information (or Computer Age), is reason enough to be interested in the preservation of books as repositories of knowledge and information. But preservation in this general sense is not Purcell's subject. She's not simply writing an elegy to the book as cultural artifact; she's exploring the visual field of that disintegration for clues and qualities which can transcend the mere concern for its loss--as, literally, unsuspected aesthetic values, finding meaning in the entropic slump of matter, oppressed by the weight of our desire and frustration and neglect, the material consequence of the inertia of intent which our civilization has built up, over centuries.

Caches of such detritus are everywhere, one has only to look beyond the shopping centers and freeway overpasses to discover the neglected, rejected, strewn, cast-off, forgotten, abandoned, lost, hidden, used-up, thrown-away, scattered, buried, stashed, saved, deconstructed and appraised stuff--lying everywhere about us on this grizzled, ancient planet we call home. Purcell is a collector, and the more complex, dense and churned the things she finds are, the more she is fascinated and drawn to them.

The spaces we inhabit in our imaginations--in our dreams, or our speculations about the structure of memory, or of our thought and sensation--may be expressed by the piecemeal disintegration of physical matter, the valence of which follows predictable and inevitable laws of process. Our familiar tendency in the presence of the weight and strata of decay is to experience fear, revulsion, dismissal. But we know that decay, oxidation, compression, dispersal are in fact the harbingers of renewal, of the process of the restoration of stasis, fertile ground for the cycles of re-use, the eternal plant.

Decay, invasive corruption and consumption penetrate and eat away at the edges of intention, desire, feeding a hunger that has no name. There is a beauty in the implosions of matter, the vivid transformation, chemical, fragmented, delicate screens of digest(ion), riddled, organic, bitter and sweet, obdurate and fragile.

Is sour the desire of sugar? Do we salvage to sing? Sacrifice excess lots to crunch skeletons of structure? The material text burned onto tablets of sand, glass lens interpolating distortions of the known. As we lose these masses, flickers of light illuminate the pyramid of resistance, what endures in the circus of chaotic species. Climax decay.

The deconstruction of disabled formal artifacts suggests abstraction. Meaning gathers around nodes of familiar keys, echoes, clues. But these are all familiar fragments. Within the span of cultural memory, we're on solid ground. But nothing could be less confirming.

The deconstruction of disabled formal artifacts suggests abstraction. Meaning gathers around nodes of familiar keys, echoes, clues. But these are all familiar fragments. Within the span of cultural memory, we're on solid ground. But nothing could be less confirming.

Decay, invasive corruption and consumption penetrate and eat away at the edges of intention, desire, feeding a hunger that has no name. There is a beauty in the implosions of matter, the vivid transformation, chemical, fragmented, delicate screens of digest(ion), riddled, organic, bitter and sweet, obdurate and fragile.

The disintegrating vestiges of surface-meaning challenge our notions of use, cause our conceptions of the value of such surfaces to undergo a relentless intellectual composting. Purcell notices that photography, the momentary and impulsive fixing of such surfaces through the poised, controlled exposure, can preserve moments of this process. In the campaign of her documentation, richly grained and evocative, the foamy churning of digested matter becomes lush, hypnotic and weird.

Is sour the desire of sugar? Do we salvage to sing? Sacrifice excess lots to crunch skeletons of structure? The material text burned onto tablets of sand, glass lens interpolating distortions of the known. As we lose these masses, flickers of light illuminate the pyramid of resistance, what endures in the circus of chaotic species. Climax decay.

The deconstruction of disabled formal artifacts suggests abstraction. Meaning gathers around nodes of familiar keys, echoes, clues. But these are all familiar fragments. Within the span of cultural memory, we're on solid ground. But nothing could be less confirming.

The deconstruction of disabled formal artifacts suggests abstraction. Meaning gathers around nodes of familiar keys, echoes, clues. But these are all familiar fragments. Within the span of cultural memory, we're on solid ground. But nothing could be less confirming.

The orgasm of progress stockpiles products of excess labor. The mind window-shops for stuffed mannikins of abandoned weaves, plastic body parts. Connoisseurs of industrial detritus. Symbiotic companions contract out parasitic eyeless wormlike hoards jiggling through the logarithm of rising fizz.

In my earlier posts on Irving Penn and Frederick Sommer, I explored the metaphorical implications of the use of light-sensitive surfaces to bear the self-reflexive relationship between viewer and object, eye and subject. Light is a medium, but it is also acomponent of matter itself--perhaps, as physicists now believe, the very stuff of matter itself. Light is not only the transmitter of data (of meaning), but also--in its other manifestation as "arrested light" the sensitive surface itself--matter talking to itself. And that is a conversation we sometimes may seem to be overhearing. Some such sense of the overheard seems to be taking place in Purcell's elegant color prints. Carpe diem. In seizing the momentary evidence of the degraded artifacts of our ambitious culture of production, Purcell is holding time to account, demanding of our impatient circumambient distraction, that we pay heed.

There's a lush permission about these images in Bookworm, as if we had tunneled into the Pharaoh's tomb, and held the brittle papyrus scroll in our quivering fingers. Our fortunes may be read from just such fleeting formulae. We are shadows and ghosts. The evidence of our having existed, pales in significance to the grander panorama of geologic time.

The overwhelming materiality of the quotidian masquerades as random thought, but animation may simply be a projection of a mindless consumption. Form is used up in a circle drawn by the fixed idea. The orbit of anxiety is constantly decaying. Language might decompose at the same rate as attention. We race entropy to the finish line.

The overwhelming materiality of the quotidian masquerades as random thought, but animation may simply be a projection of a mindless consumption. Form is used up in a circle drawn by the fixed idea. The orbit of anxiety is constantly decaying. Language might decompose at the same rate as attention. We race entropy to the finish line.

Rosamund Purcell

What is Post-Utopian Urbanism? Urbanism, Utopias, Urbatopia (guest post 1/3)

http://ladialectique.wordpress.com/2011/08/23/what-is-a-post-utopian-urbanism-urbanism-utopias-urbatopia-13/

Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre’s Ruins of Detroit is a series of photographs

Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre’s Ruins of Detroit is a series of photographs

documenting the long-going crisis and urban decay of Detroit, MI

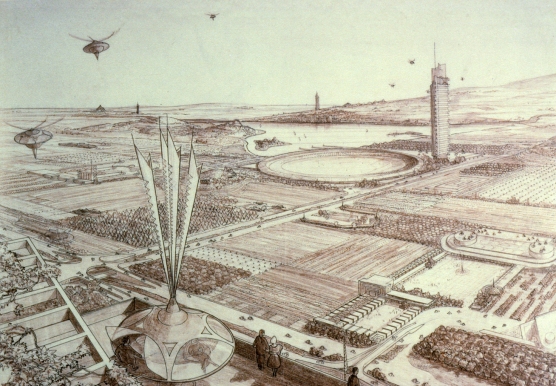

Frank L. Wright’s “Broadacre City” is a model for suburban development. He introduced the utopia in hisDisappearing City, published in 1932.

Frank L. Wright’s “Broadacre City” is a model for suburban development. He introduced the utopia in hisDisappearing City, published in 1932.

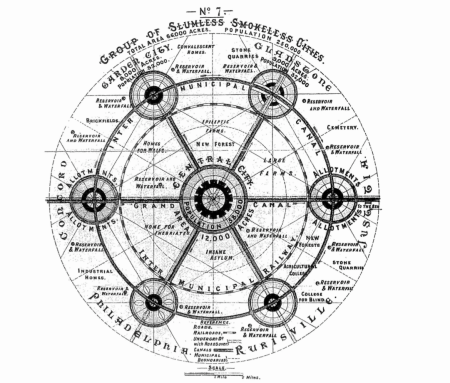

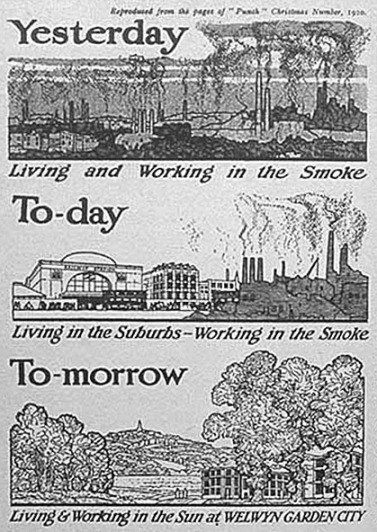

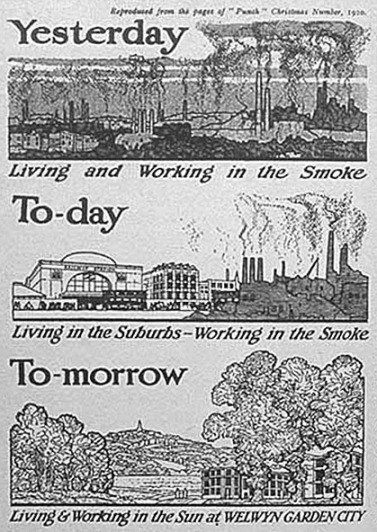

Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of To-morrow (1898),

Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of To-morrow (1898),

another example of the antipathy vis-à-vis the City underpinning the concept of Garden Cities

WHAT IS POST-UTOPIAN URBANISM? URBANISM, UTOPIAS, URBATOPIA (GUEST POST 1/3)

When “God is dead, the author is dead, history is dead, only the architect is left standing” (Koolhaas, 2002: 18) without utopias, what (or who) is actually left for the planning and development of our cities?

Besides its appeal to a longue durée analysis, the topic of urbanism and utopia – and their links, of course – is today rather fashionable, whether one speaks of current exhibitions, critical insights on the idea of acapitalist Utopia, or even indirectly among the latest parliamentary reports.

In this series of three guests posts we will explore the definition of a Post-Utopian Urbanism, on the basis of various readings ranging from Lefebvre to recent writings of Jameson and Rem Koolhaas, and to a great extent indebted to David Harvey’s seminal analysis of the links between capitalist transformation and our (post)modern perception of space and time (1989).

The enterprise of surveying the intimate relationship between Urbanism and Utopia consists of reading the dynamics and transformations that affected cities and their planning over the centuries, together with the discourse surrounding this practice. Put otherwise, the topic at hand here is one of epistemological concern, and is conducive to a two-part analysis: it is as much a study of the urbs, the City itself, as of urbanism, the self-reflective scientific discourse underpinning the city’s development.

The definition of Utopia, the City, and the contextualisation of their problematic encounter is a controversial undertaking. Despite the canonicisation of utopian literature through Thomas More, there is no strict consensus on what a utopia is. And the task of tracing the archaeology of that which makes a City, and of that which makes possible its existence through planning and building, is equally broad and subject to debate. In what follows, the many links between the two will be scrutinized, with special attention paid to the tensions inherent to these links.

Postmodernism as the End of History and the Crisis of Representations

Destruction of the Pruitt Igoe housing ensemble,

designed by Minoru Yamasaki in accordance with the planning principles of Le Corbusier and the International Congress of Modern Architects.

designed by Minoru Yamasaki in accordance with the planning principles of Le Corbusier and the International Congress of Modern Architects.

St Louis, Missouri, 1972

We can deal with the topic as an exercise of reading the “City” as an object through time: on the one hand, with reference to the transformations that have affected empirical practices and discourses of the planning métier; and on the other hand, by analysing the capacity of this object to embody and be the scene for social change – whether simply aiming to produce otherness, or, more ambitiously, to proceed towards betterment. This ability for ‘change’ came into question around the 1970s, as urbanism gradually divorced from the modernist project of utopia, one based on a ‘science’ of social improvement through technical progress.

In his comprehensive and insightful survey of ‘postmodernity’ – a key concept in understanding the development of post-utopian urbanism – David Harvey recalls the anecdote of Charles Jencks, whoseLanguage of post-modern architecture (1984) indicates 3.32 p.m. the 15th of July 1972 to be the precise moment marking the death of modernity, and the subsequent passage into postmodernity. At this date, Yamasaki’s Pruitt Igoe complex was torn down.

Besides its aesthetic dimension, we find this photograph compelling. Firstly, for what it represents: the fall of modern urbanism (Choay 1965), which had considered scientific progress as a utopian engine. And secondly, for the crisis it forewarns: precisely of our contemporary difficulty to represent things. For indeed, to survey the changes affecting urbanism and utopias in their kinship is to study nothing but thecrisis of representations: whether it is that of politics (crisis of liberal democracies and of the link between governing bodies and the governed); that of technique (crisis of the economic and urban plan); that of architecture (crisis of comprehensive projects, giving way to an aesthetic of collage, and small scale); or that of social representations (crisis of the pluralist society, the dissolution of unitary identities), and so on (Harvey 1989, MacLeod et Ward 2002, Pinson 2009).

Historically, this crisis of representations had been gaining momentum since the 1970s, riding the wave of a broader set of social and economic troubles. At first an economic crisis, it then spread, whether in a causal chain or in concomitance, to various spheres, and may nowadays lead us to wonder if the one-time crisis has not became the norm of our societies, in a transformation similar to what Agamben (2005) noted about the state of exception in liberal democracies.

Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre’s Ruins of Detroit is a series of photographs

Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre’s Ruins of Detroit is a series of photographsdocumenting the long-going crisis and urban decay of Detroit, MI

Urbanism versus Utopia? An Etymological Inquiry

In order to study the many ways in which urbanism and utopia work together, and to bring in to light the resultant tensions, let us start with a brief self-sufficient definition. At first glance, urbanism and utopia appear to operate within different ontological spheres. The former literally deals with concrete matter, in the sense of buildings and infrastructures, whereas the latter operates necessarily in the domain of speculative abstraction.

‘Urbanism,’ at least in French, is rather recent; it was born in 1910 as the “science and theory of human establishment” (Choay, 1965: 8). As its etymology implies, it is the science of the urbs; Latin word for the walled city, the solid city then, as founded by Romulus when he traced down the limits of what was to become Rome. The fact that the birth of ‘urbanism’ is connate with the Industrial Revolution is anything but fortuitous. It reflects the historical turn from the country to the city, where today the vast majority of the world’s population lives. As a ‘science’, urbanism became a discipline per se: with its own tools, its own history, and its own discourse. It is important that urbanism’s ‘scientific’ status not obfuscate its deep political involvement: its object is no less than the form of the communal life that takes place in the immense ensembles, whose density distinguishes them from the country. It is in this attempt to condition the dynamics of communal life that urbanism finds its kinship to utopia.

On the other hand, utopia is first a literary genre, one that can be traced back to Plato’s Republic but which seems to have acquired its canonical status in Thomas More’s eponymous book, published in 1516, before being strongly developed during the 19th century among early socialists like Proudhon, Ledru-Rollin, Herzen and Fourier. The utopian gesture is characterised by its force of projection; it ‘throws’ two visions of a topos, together into a single place. On the one hand, outopia (οὐ τόπος), a nowhere: an-otherland that does not exist. And on the other, eutopia (εὖ τόπος), a better or good place: one in which harmony prevails (Choay 1965, 25). Utopia thereby articulates a capacity of abstraction with moral insights.

Urbanism + Utopias = Urbatopia?

The City functions as the privileged nexus in which urbanism and utopia enter into contact. As mentioned, the fundamental common ground of urbanism and utopianism consists in their attempt to condition the harmonious community, the vivre ensemble. We can sketch this common ground along four more registers.

- Throughout their history, urbanism and utopias have shared a reliance on a spatial basis: they imagine and lay down the principles of organizations for ideal places, that is, power relations between groups that are embedded in a given territorial conception (Choay 1965, Harvey 2000).

- In their practice – or operational mode – urbanism and utopias partake in the dialectical gesture of projection. By abstracting from the here and the now, they both seek to lay out a legible space, one that does not yet exist but might. Such projections are generic – models capable of being reproduced (Choay 1965, 25). This “spatial game” (Harvey 2000) projects an-other space. In such a way, urbanism until the 1970s, equated this ‘otherness’ with betterment: its utopias conveyed a sense of social and moral progress. Here it is important to signal the centrality of repetition in utopian and urban projection, an aspect of their model-oriented production. Are utopias – as models at once generic but virtuous – suitable to reproduction, or are they unique? Put otherwise, can they be reproduced independently of the context in which they were conceived?

- This in turn raises the question of the third feature on our list: totality. This common concern of both utopian and urban practices explicitly appeals to the issue of openness in political regimes, and that of political theory more generally (Jameson 2004). Generally speaking, utopias conceive closed and self-sufficient spaces, not foreign to the etymological notion of the walledurbs. Today however, the forms of our metropolises or edge cities seriously hamper this capacity for self-enclosure.

- Last but not least, urbanism and utopias are united in crisis, as presaged by the photography ofPruitt Igoe’s destruction. In the late 1970s and early 1980s the twofold crisis – of capitalist economies and liberal democracies on the one hand, and of any alternative to these systems, on the other – was mirrored in the crisis of urban societies (Pinson 2009). The ‘crisis of the plan’, whether economic in the Keynesian doctrine, or urban/strategic in the practice of zoning, epitomizes this predicament.

It is on the basis of these four points of contact between utopias and urbanism (space, projection, totality and crisis) that we seek to conceive of a post-utopian urbanism.

Motifs in Urbanism: The shift from Urbatopias to Urban Dystopias

This attempt, though interesting, should not preclude a brief examination of the contradictions within the very objects of inquiry themselves (Harvey 1989), and their dynamics. Indeed, the term ‘urbanism’ may sound strange to the Anglo-Saxon ear, accustomed rather to the term ‘urban planning.’ This semantic difference encapsulates quite succinctly the dramatic shift in the discipline, the original attempts at ‘planning’ having been confronted with, and to some extent superseded by, ‘design’ (Rode 2006), related to the fading away of utopias.*

This echoes Antoine Picon’s statement that urbanism is nothing but “a series of historically determined propositions” (2004: 4; our translation), suggesting the need to understand the widening rift between planning and the modernist utopia within the socio-economic context that urbanism inhabits (Harvey 1989).

Frank L. Wright’s “Broadacre City” is a model for suburban development. He introduced the utopia in hisDisappearing City, published in 1932.

Frank L. Wright’s “Broadacre City” is a model for suburban development. He introduced the utopia in hisDisappearing City, published in 1932.

Born as a clear-cut motif in the academic literature and among planners around the turn of the 1970s, Dystopia points to the anti-urban dimension of a whole school of previous utopias, ‘initiated’ by Frank L. Wright. While the term ‘school’ may be far-fetched, this planning tradition presents identifiable traits based on a common denominator: the formal disappearance of the City, with its centrality and industrial nuisances, superseded by small, decentralized, and multipolar introductions of nature in Garden Cities (Choay 1965).

Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of To-morrow (1898),

Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of To-morrow (1898),another example of the antipathy vis-à-vis the City underpinning the concept of Garden Cities

This repugnance vis-à-vis the city is discernable in the postmodern understanding of dystopia. This is true of the U.S., where the avatars of urban studies’ nightmares abound: Los Angeles, Las Vegas, edge cities, gated communities, and, of course, the hyperghetto (MacLeod et Ward 2002, Pinder 2002). The appearance of this dystopian figure is anything but fortuitous. It is deeply rooted in the crisis of the 1970s and develops parallel to the apparition of postmodernism in the aesthetic and academic domains.

The city, once the nexus through which urbanism and utopias worked together towards betterment through the Keynesian mode of regulation (Harvey 1989, Pinson 2009), seems to have become the place of all nightmares: segregation, endemic crime, socio-economic inequalities. Where the projects once offered a shelter to the dispossessed of the inner-cities, there are now to be lofts and branches of globalized brands. This historical shift deserves substantial attention, for it is the nexus of understanding how, and maybe why, urbanism departed from utopias and thus went from planning to design, from comprehensive projects to a small scale-based architecture of collage, and from the plan able to regulate – for a time – the contradiction of capitalism to the ‘urban project,’ whose object is now the undecipherable city as a whole (on the notion of urban projects, see Pinson 2009). It will also allow us to examine the embedded nature of this shift in a greater capitalist evolution (Harvey 1989).

The divorce between urbanism and utopias is indeed inextricably linked to, and may be the expression of, the inability of the urban society to regulate the inner contradictions of capitalism and the subsequent growth of inequalities. The next step in understanding what could be a Post-Utopian Urbanism will therefore focus on the shift from Urbatopia to Dystopia, so to speak, and examine the consequences and implications for the ‘plan’ as a scientific tool, and by extension for urbanism.

* to go further on the distinction between ‘planning’ and ‘design,’ see Rode “City Design — A New Planning Paradigm?” (2006). See also David Harvey’s major work on postmodernity and its passages on the aesthetic of collage, pp. 40-60 and chap. 4.

WEATHERING (P_WALL)

http://matsysdesign.com/tag/wall/

WEATHERING (P_WALL)

Year: 2009

Location: Not in a gallery

Location: Not in a gallery

Description: The process of weathering is often intentionally resisted (if not completely forgotten) in most contemporary design. This is a legacy of Modernism and its fascination with minimal, timeless, and antiseptic materials. David Leatherbarrow and Mohsen Mostafavi have done an excellent job of mining this ground through architectural history in their book On Weathering (1993). They reveal in this book a long tradition in the design world of working with the act of weathering in a way that enhances the design concept over time. Rather than design in a way that presents the Sisyphean task of negating the influence of time on a project, they document other strategies architects have taken to accept that their buildings will have a life of their own after the drawing board.

This concept has been hovering in the background during the evolution of P_Wall (2006 / 2009) over the last 3 years. When people see the wall, they seem to have an inherent desire to touch it. The hint of softness, the evocative forms, the fabric textures all draw people in, seducing them to feel its rounded curves and deep creases. After each time it has been exhibited, a certain patina can be seen on the pieces: fingerprints here and there, scuffs from handling, etc.

This projects explores the potential weathering of P_Wall. Beyond the simple marks of humans in a gallery environment, the wall is located outside, open to the elements. The undulating forms would collect dust, pollen, soot over time. Moss would take root in the subtle groves of the fabric texture. Birds and other creatures would make the holes their homes.

This is not an exercise in Romanticism. The goal is not to produce a picturesque image of the wall. Rather, there is something about the wall that craves to be touched, to be made unclean, to be used, worn, soiled. Throughout the fabrication of the tiles, spiders would constantly be found making the holes their traps. A fine layer of soot, plaster and saw dust seemed to be constantly attached to the forms. This project accepts these intrusions on the “pure” form and makes them apart of the design. No more resistance, P_Wall accepts the life of the world and changes with it.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)